✺

On Stories and Histories: Q&A

Tell me what you think of this—I have a theory for why everything is going wrong…

“GIOIA: Well, it’s interesting. In the modern movement, and I’m talking about maybe 1914 to the Second World War, there was a huge transformation in all the arts, music, sculpture, painting, literature, and art became, in every form, more abstract, more conceptual, more formal, not in a sense of rhyme and meter or whatever but in terms of these structural designs. As part of that, there was a general bias against narrative. Putting a story in was somehow condescending to a stupid audience but the fact is, humanity needs stories. People lead their individual life as a storyWow I mean we might. One of the reasons you need lots of stories is that in every life, your story comes to an impasse.

You have to, in a sense, revise the narrative of your own life, and what fiction does, what poetry does, what narrative does is give you a wealth of narrative possibilities so you can recognize that no matter how bad your life is right now, that there’s an escape, there’s a rescue, there might even, in the Greek sense, be a deus ex machina, an intervention which saves you. I believe that the suicide epidemic in the United States, the opioid epidemic in the United States, especially among young people, is among people who cannot, in a sense, get control of the stories of their own lives.

The deprivation of narrative in stories, the cheapening of narratives in our mass culture, I think has had tremendous human cost, both in the loss of creativity, loss of productivity, and also, at its worst in terms of suicide, drug use, and death.”

— Conversations with Tyler, “Dana Gioia on Becoming an Information Billionaire (Ep. 119)”

I: Stories

Q: Tell me what you think of this–I have a theory for why everything is going wrong…

A: Of course you do.

Q: …why deaths of despair (suicide, addiction) are on the rise, why extremism of seemingly all kinds (white nationalism, wokeism, religious fundamentalism, QAnon and other conspiracy theories, anti-semitism, etc.) has never been higher, why we can’t seem to produce great art anymore, why innovation is slowing down, why…

A: Okay okay, I get the idea. What’s this grand “Theory of Everything” then?

Q: All of these issues are arising in part from a degeneration of what we might call our narrative faculties.

A: Yeah, I’m going to need you to unpack that a little bit.

Q: The computational sociologist Jacob Foster has some interesting preliminary work on a theme which he calls “a social science of the possible”, something which as far as I can tell he has only spoken about once in a 2021 talk at the Institute of Advanced Study. One of the things that Foster is interested in with this “social science of the possible” is the role of stories in shaping society, particularly how stories shape the emergence of novel collective behaviors in response to novel circumstances. As he tells it, we have basically two ways of responding to any situation, “model-free” and “model-based”, which corresponds roughly to habitual and deliberative responses. The problem arises when we are faced with an unprecedented situation for which our habits and prior lived experience are of little use. What then? How do we decide what to do? This is where stories come in.

Foster defines stories in the simplest possible terms, as some initial state, an action which is performed, and a result—in this situation, if you do X then Y will happen. A story in this sense can be a fictional story, but it can also be an account of another person’s experience, a historical episode, a scientific study or theory, essentially anything in which one can draw this situation, action, result sequence (s, a, r). With this definition in hand, Foster proposes a simple model:

(s, a, r) K(s, s`)

in which the second term is an index that measures the similarity between a given situation s’ and the situation in your story s. From this model, Foster derives a simple insight: people coordinate in novel situations by agreeing upon which stories are most relevant and then using those stories to guide collective action.

Foster is primarily interested in the collective level, but the general logic of the model applies to individuals as well—that is, a person’s ability to respond creatively and adaptively to life’s vicissitudes depends on two factors: (1) the size and diversity of their story database and (2) their ability to assess the relevance of a story to a given situation. Both factors are important of course, but (2) has less to do with stories per se and more to do with intelligence or a kind of wisdom (can you identify the key variables of your situation and match them to a story that you know of?); so when I speak of “narrative faculties” I am really referring more to (1), something like—the imagination, resilience, and sense of personal agency that are supported by a varied and plentiful “diet” of stories.

A: So if I’m understanding you correctly, the idea is that poor story diets (and poor food diets for that matter) are leaving more and more of us unable to respond to the many challenges of modern life in a positive manner, which is in turn leaving more and more of us susceptible to depression, addiction, and the various extremist ideologies on offer.

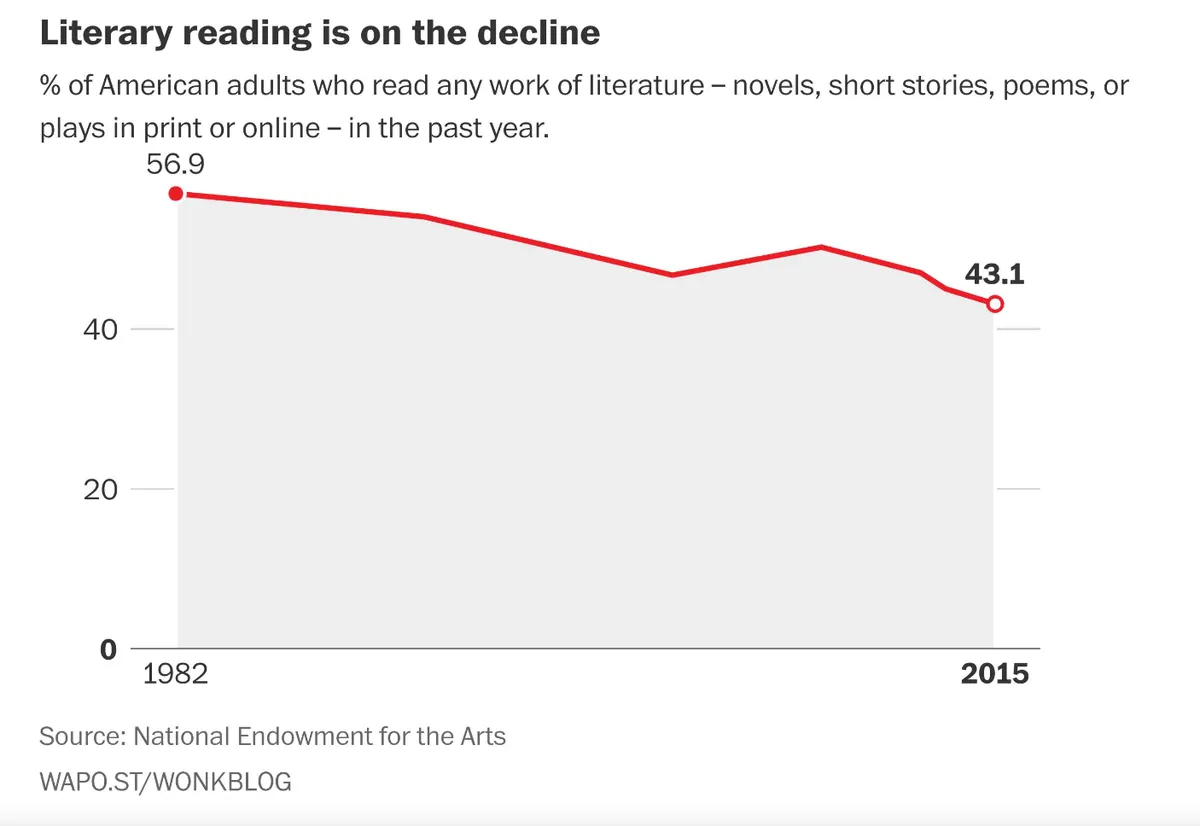

Q: Yes, something like that. So the real question is why aren’t we getting enough narrative nutrients? For one, we probably just aren't “eating” enough—Americans are reading fewer books (from 15.3 per year in 1991 to 12.6 in 2021 according to a Gallup poll) and less literature than ever before.

Of course books aren’t the only way one can “eat” stories, but they do allow for a level of nutrition, of narrative richness and emotional depth, that is hard to find in other mediums. As for film, the endless stream of reality shows, superhero movies, and sequels or spinoffs thereof amounts to nothing more than junk food, Mcdonald’s for your mind. Video games do offer tremendous opportunities for story-telling, but that is rarely the focus, and the same could be said for podcasts—most of it junk food.

I believe that we are, as a country and a culture, beginning to see the effects of this narrative malnourishment. The rise of Trump and our current state of polarization is not the least bit surprising to me given the preponderance of hero worship and simplistic good vs evil plotlines in the story diet of your typical american.

A: There’s probably some truth in all of that, but I wonder if there is also something deeper going on here. Not all stories are created equal, right? National, cultural, and religious narratives are not just data from which you can draw potential actions or “calories” from which you draw strength, they provide the setting (the story-world) in which your personal plot is set, they define who you are as a character and who you might be in the future, “We awoke in the morning and knew where we were” (Thomas Berry). We might say that stories of this kind are not just food for your mind, but also for your soul.

We all want our lives to be exciting and dramatic, but what happens when the overarching narrative of your life gives you very little to work with, no conflict, no mystery, no nothing? Well, you start looking for conflict, for drama of any kind, anything that can spice up your life and explain why it isn't as captivating or fulfilling as you hoped it would be. Maybe you start believing that there is some nefarious conspiracy to keep you and your people down, or maybe you just try to numb the pain with entertainment and hedonism. And if you can't or won’t do either of those things, then well…

I think the historian Jacques Barzun was onto something when he quipped that “Boredom and fatigue are great historical forces.”[1] There are over 210 theories for why the Roman empire collapsed, but here’s another one: the Roman soap opera became stale and people wanted to watch something else. I would contend that the same is happening right now with the American sitcom (and yes it’s a sitcom).

Humor me: let's review the “plot” of American history,

Season 1: The Revolutionary War, the birth of a nation, war of 1812, westward expansion, manifest destiny

Season 2: The Civil War, reconstruction, racism, immigration, continuing westward expansion, rising in prominence on the world stage

Season 3: Turn of the century, WWI, more immigration, becoming a major player on the world stage, the roaring 20’s, the great depression

Season 4: WWII, attainment of world superpower status, The Cold War, the Korean War, the civil rights movement, the hippies, The Vietnam War, The collapse of the USSR

Season 5: Y2K, 9/11 and the warr on terror, the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, the rise of China, the Great Recession, COVID-19 (everyone’s least favorite story arc ever), BLM/George Floyd

This is the worst season yet and I don’t even think it’s debatable.

All of the Season 5 plotlines feel re-hashed (we already did the “protracted unwinnable war” thing in Vietnam and it sucked, not sure why we thought changing the setting to Afghanistan would be any different), and even the ones that seemed promising at first ended up being rather anticlimactic. The cast—the main characters and all the extras–are aging and not bringing the same energy to their performances. We even tried to spice up the show by bringing in an established reality TV star, but that only made things worse.

Of course this is all a bit silly, and I'm not suggesting that anyone is thinking about this quite so literally, but I do think that a kind of boredom or fatigue with the American story has set in and that it’s contributing to this broader malaise we’ve been discussing.

Q: It strikes me that you could also speak of the US as a character in the global historical drama (“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances”). From our first appearance on the show in 1776 until WWII, we were the plucky upstart, the underdog, and everyone loves a good underdog story, right? After losing underdog status, we immediately transitioned into the Cold War plotline—a clear good vs. evil dynamic. Now what do we have? Our character just isn't that interesting or charismatic anymore, and it feels like the entire world is ready for something new.

A: It also probably bears mentioning that the United States isn’t one giant monolith—individual ethnic groups and identities (different “characters”) may still have very exciting and galvanizing stories even if the larger American narrative is getting a little stale.

Although America as a whole may have lost its underdog status, minorities, immigrants, women, and LGBT people can still lay claim to it (rightfully in some cases, in others not so much). It’s interesting to note that most of the issues we’ve been discussing here—the various extremisms, the so-called deaths of despair—seem to be disproportionately affecting white Americans, especially white men, the only demographic group for whom suicide rates are still rising, for example. Does it seem reasonable to think that the white American story has gotten particularly tiresome and uninspiring? I think so.

Q: Yeah I think so, too. Even though there are many white Americans that can rightfully claim to be underdogs in some sense, it's not a narrative that mainstream culture wants to acknowledge, for obvious reasons given the privilege that many white people have benefited from in the recent and distant past. Most white Americans also lack any other ethnic narrative from which they can draw identity and heritage—after generations and generations of mixing, any claims of being Irish-American or German-American are tenuous and superficial at best for most. Add all of this together and you have a group of people that feel culturally and historically unmoored, adrift in a story-world that doesn’t really give them any especially lively or inspiring material to work with for their own personal narrative.

At the risk of trying to explain everything and thus failing to explain anything (something we've probably already done), I would argue that many of the new ideologies which some white Americans are embracing to an almost pathological level as a natural response to this lack of meaningful narrative. Wokeism provides a nice story—you are working to rectify the sins of the past; it always feels good to feel like you are standing on the right side of history, right? Or maybe you flip the script and lean into the narrative that liberals and their institutions are oppressing you and trying to get rid of your way of life. Maybe you look around and see that every other minority takes pride in their story and you start to wonder why whiteness can't be something you take pride in.

None of this is to say that there isn't some truth in all these stories. Social injustice does exist of course and coastal liberals do look down their noses at religious conservatives in the “flyover states”. Whiteness doesn’t necessarily make sense as a basis for shared identity in the way that it does for American minority ethnic groups (e.g. Asian-Americans), but there is much in European and broader Western tradition to be proud of. The problem is when these narratives become totalizing and form the only lens through which you can see the world.

II. Histories

Q: Can we talk about Nietzsche?

A: Sure.

Q: Many of the ideas and themes from one of his earlier essays, “On The Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life” (1874) feels very relevant here. To Nietzsche, history must always be in service of life. Of course a person or a culture can have a deficiency of history–this is essentially what we’ve been discussing here; Nietzsche places the value of history in, “the sense of well being of a tree for its roots, the happiness to know oneself in a manner not entirely arbitrary and accidental, but as someone who has grown out of a past, as an heir, flower, and fruit, and thus to have one's existence excused, indeed justified, this is what people nowadays lovingly describe as the real historical sense.” Without these roots, he argues, we become “a people which has lost faith in its ancient history and has fallen into a restless cosmopolitan choice and a constant search for novelty after novelty” (sound familiar?[2]). In contrast, we can easily suffer from too much history, “There is a degree of insomnia, of rumination, of the historical sense, through which living comes to harm and finally is destroyed, whether it is a person or a people or a culture.” Over-development of this historical sense can make it difficult for us to move forward and begin anew; it can restrict our imagination and ambition, tricking us into thinking that we know, once and for all, what humans are or what they are capable of. To think that knowledge of history is valuable in and of itself is a terrible mistake, “we must seriously despise instruction without vitality, knowledge which enervates activity, and history as an expensive surplus of knowledge and a luxury, because we lack what is still most essential to us and because what is superfluous is hostile to what is essential.”

Nietzsche goes on to identify three different methods of history: the monumental method, the antiquarian, and the critical. The monumental is the method of looking back at history for ideals and exemplars, for sources of inspiration, “The greatest moments in the struggle of single individuals make up a chain, in which a range of mountains of humanity are joined over thousands of years. For me the loftiest thing of such a moment from the distant past is bright and great–that is the basic idea of the faith in humanity which expresses itself in the demand for a monumental history.” The antiquarian mode is that impulse to preserve and honor history, to value tradition and custom for their own sake:

“The history of his city becomes for him the history of his own self. He understands the walls, the turreted gate, the dictate of the city council, and the folk festival, like an illustrated diary of his youth, and he rediscovers for himself in all this his force, his purpose, his passion, his opinion, his foolishness, and his bad habits. He says to himself, here one could live, for here one may live, and here one can go on living, because we endure and do not collapse overnight.”

The critical method is exactly what it sounds like, “dragging the past before the court of justice, investigating it meticulously, and finally condemning it”. The critical is valuable because sometimes the past is unjust and does deserve to be destroyed.

Each of these historical modes is important and we suffer when any of them becomes too dominant. Taken too far, the monumental becomes hagiography, the Great Man theory of history. The antiquarian’s weakness is that it always undervalues what is coming into being; conservation of the past becomes mummification.[3] An excess of the critical can lead to arrogant attempts at replacing tradition without an understanding of why the tradition exists in the first place (i.e. Chesterton’s Fence). Conversely, the critical can also fail to serve life by making it hard for us to let go of grievances and past mistakes.

A: Hmm so if we had to put our previous discussion in Nietzsche’s framing, I guess we would say that our culture is suffering from an excess of the critical method and a deficiency of the monumental and the antiquarian. In some sense, we simultaneously have too much history and not enough of it.

Q: Yeah, I think that’s right. The next question is how did we get here?

A: The postmodern turn in the academic humanities, with its skepticism towards grand narratives and emphasis on the deconstruction of all ideologies and institutions, is partly to blame. I suspect that's only part of the story however, because it feels like this problematic relationship to history is a more recent phenomenon and postmodernism first became ascendant in the 60s and 70s.

The Internet and digital technology more broadly would seem to be an obvious culprit here. Our historical sense has become grotesquely overgrown. The entire archive of mankind’s past is at our fingertips. Nothing fades away anymore; all events, large and small, become permanently crystallized into ravenous, ever-growing databases. It's too difficult to let past injustices go when you can refresh your memory with a few clicks and it's too easy to tear down anyone who is practicing the monumental mode by glorifying some historical person, movement, or event. You know that thing where you meet your childhood hero, but then you wish you hadn’t because you realize they are an asshole? It’s like that, except now we've met every hero ever and realized they are all assholes. At the same time, we are also completely inundated by new content of all kinds—new emails, new tweets, new blog posts, new scientific articles.[4] There is too much “now” happening and it's causing our historical sense to degenerate; more than ever, we are prisoners of the moment, spellbound by the Current Thing.

All of this has bred a dangerous cynicism into our culture, a sense that ideas are getting harder to find, that “nothing is cool” anymore.

“I believe that the progressive fervor of the humanities, while it reenergized inquiry in the 1980s and has since inspired countless valid lines of inquiry, masks a second-order complex that is all about the thrill of destruction. In the name of critique, anything except critique can be invaded or denatured… you could say that what is cool now is, simply, nothing. Decades of anti humanist one-upmanship have left the profession with a fascination for shaking the value out of what seems human, alive, and whole.[5]”

Taken together, these forces—post-modern cynicism and the broader historical and narrative maladies that we’ve been discussing—are responsible for the current creative malaise in the arts and sciences.

The crushing excess of new content is especially problematic in this regard. We have less familiarity with the deep history of art and culture than ever before, and this has caused us to lose a kind of instinct for Greatness–an intuition for what makes things stand the test of time. At the same time, most of us also have too much knowledge of our chosen art or discipline and this makes it difficult for us to do the unprecedented, path-breaking work that revolutionizes a field. In the arts, the danger is that everything you make will feel derivative, a pale imitation of yesteryear’s avant garde. In the sciences, an extensive knowledge of the literature will bias you towards conducting incremental gap-filling research instead of the truly innovative research which creates new gaps in the literature. Richard Hamming has a little riff on this in his classic speech, “You and Your Research”:

“There was a fellow at Bell Labs, a very, very, smart guy. He was always in the library; he read everything. If you wanted references, you went to him and he gave you all kinds of references. But in the middle of forming these theories, I formed a proposition: there would be no effect named after him in the long run. He is now retired from Bell Labs and is an Adjunct Professor. He was very valuable; I'm not questioning that. He wrote some very good Physical Review articles; but there's no effect named after him because he read too much.”

So there is reason to think we just aren’t as creative and innovative as we once were, but I also think part of the problem is inspirational and aspirational. The lack of compelling cultural narratives leaves many of us with nothing but personal motivations for achieving greatness of some kind. Motivation to achieve greatness for one’s self is one thing, but motivation to achieve greatness for one’s community, culture, or country is another, a purer and potentially even more powerful form of inspiration. As a random example, I recently watched a documentary about Linsanity, the meteoric rise of Jeremy Lin to temporary NBA stardom with the New York Knicks. He was of course highly motivated for personal reasons seeing as he was a fringe NBA player who hadn't yet proven himself on the big stage, but Lin himself believes that the extra drive he got from being the first Asian-American NBA player made all the difference.

III. Rekindling

A: I have to run in a few minutes, so let's talk solutions. What can be done about all of this?

Q: To recap, there are really three separate issues which we have discussed: the atrophying of our narrative faculties, our boredom with the available national and cultural narratives, and this Nietzschean historical sickness caused by an excess of the critical mode of history and a deficit of the monumental and antiquarian.

Regarding the atrophying of our narrative faculties, there are a bunch of facile and frankly pretentious suggestions I could make here about how we need to teach more literature in schools or teach it in a different way (“Literature Should Be Taught Like Science!”), or how hollywood needs to start making more sophisticated films, but these suggestions have already been made countless times and are not really actionable for anyone except for school superintendents or big-shot movie producers I suppose. Maybe some small percentage of those listening in on our conversation will be inspired by our discussion to start reading more literature and cultivating more sophisticated tastes, and sure that's great and all, but what’s really needed is something very deep-rooted, a fundamental shift in the way we produce stories and value them.

There may be one reason for optimism here: the rise of AI art could catalyze a renaissance of the physically-instantiated narrative arts—of literature, theater, opera, live storytelling—as these are the forms which AI is incapable of mimicking, or at least won’t be able to for a very long time. This may prove to be naïve or idealistic, but I can envision a scenario in which our culture evolves to place a greater premium on the value of “humanness” and the prominence of various art forms rises or falls as a result. This, to my eyes, would be a wholly positive development, one which would allow us to cultivate the imagination and resilience needed to face what will certainly be a challenge-filled 21st-century.

As for the historical sickness, there would seem to be an obvious remedy—restore the balance between the modes by increasing the emphasis on the monumental and antiquarian in our culture. In broad strokes, yes I think this is what we need, however I am skeptical about our ability to revive the monumental and the benefits of doing so—we have become too cynical and simply know too much about the failures of the past, as I’ve argued. To me, the way forward lies through antiquarianism.

The antiquarian, I remind you, is about tradition, about a reverence for history, but crucially it has a more personal flavor to it—it’s about reverence for your family, your community, your birthplace. This sets it apart from the monumental with its emphasis on extracting exemplars from the grand sweep of history, regardless of whether or not they have any kind of connection to you.

If I could broadly characterize the arc of mankind’s historical sense across history, I would say that we began with the monumental—history was written by the victors, by the Great Men who shaped the flows of civilization. As we’ve said, our current epoch is that of the critical, an age of historical destruction, both intellectually and physically. Naturally then, the coming age must be that of the antiquarian then (not to be confused with the Age of Aquarius).

In addition to balancing our historical sense, I believe that antiquarianism may also provide a means through which we might eventually relieve our boredom with the American story (or create a new one). My sense is that the next set of reinvigorating national and cultural narratives will not come from the top-down, not from governments, corporations, or the ivory tower, but from individuals and communities turning towards their own (grass)roots and strengthening them so that their branches may reach towards the skies once again.

What we need, in my estimation, is a new culture of ancestor worship. I’ll try to make this as concrete and as actionable as possible now by speaking directly to the audience: what you must do is reach into your own past, both recent and distant, and bring it forth into your life–make it visible, salient, palpable. Put the family heirlooms on display, put pictures of your ancestors on the walls, get your family together once a year and go put flowers on the graves of the deceased, including and especially the ones you never knew, for without them there wouldn’t be the ones that you did know. Nietzsche again: “His possession of his ancestors' goods changes the ideas in such a soul, for those goods are far more likely to take possession of his soul.”

Materiality is paramount here—you need to see and touch the past, even hear it if you can. One of the many problems with our current technological milieu is that it robs us of the materiality of our lives, something which contributes to this unmooring of identity and sense of feeling adrift in the world. You can’t earmark a digital book or scribble in its margins, you can’t fray its bindings from overuse, you can’t pick it up off your bookshelf on a whim and recall where you were when you read it, who you lent it too, who lent it to you (do not kid yourself, you are never giving it back). You can’t pass it on to your ancestors (I mean you could transfer the file I guess, but somehow that doesn't feel the same). Books, notebooks, phone books (remember those?), stereos, records/tapes/CDs, cameras, pictures—so much of this prosaic junk of life is now a file or an app on your phone. But it doesn’t have to be that way. With a little effort, you can start re-materializing your life—print out the photos from your vacation, buy the physical copy of the book or the album, hang on to your old junk just because it’s your old junk.

So this form of ancestor worship also includes a cherishing of your own past—after all, you might be an ancestor too one day. At the same time, the antiquarian mode isn’t limited to you and your lineage—it’s about the history of your people and your place, the land of your forefathers and foremothers, whatever that may be to you. Ground yourself, literally—Learn about municipal history, about the people who lived and laughed and cried and died on this very soil; whether they are your specific ancestors or not, they are somebody’s ancestors and they deserve your respect. Participate in “antiquated” traditions, join the local historical society, work to maintain and restore whatever makes your place unique and beautiful.

And to be clear, I do mean ancestor worship—not just a preservation of the past, but a true veneration and sacralization. Meditate on the lives of your ancestors, imagine them smiling at you and blessing you. Make a shrine and bow to it; create rituals, elaborate and simple.

We didn't talk much about it, but religion, or the lack thereof, is playing a central role in all of the issues and trends we discussed. Disaffected by secular narratives, the religiously-inclined are turning more and more towards fundamentalism and other -isms (including Trumpism); disaffected by religious narratives, secular folk are embracing secular narratives with a religious fervor; it is becoming cliché to call wokeism a religion, but there’s more than a kernel of truth to the notion. What I find hopeful about ancestor worship, at least the sort I’m advocating for, is that it’s metaphysically agnostic—you don't need to believe that your ancestors have been reincarnated or moved onto the afterlife or anything like that in order to practice it. In that sense it is inclusive to all religions while also providing an opportunity for the non-religious to worship in whatever way they feel comfortable with.

A: One obvious critique or I suppose limitation of ancestor worship is that some people are estranged from their families or ashamed of them for various reasons, perhaps because of past abuse for example. What would you say to those people?

Q: Well for one, I hope I made it clear that ancestor worship can also have local and personal dimensions, and so if someone has an issue with their family or doesn’t really have much of one, they might place greater emphasis on their own personal history or that of their community. That being said, the point is well taken—there are people who will find it very difficult or impossible to draw strength and meaning from their personal past. To them, I would say: draw it from the future instead.

I noted this in passing above, but one of the virtues of ancestor worship is that it has a self-fulfilling quality—if you begin to practice it and pass it on to your descendants then you will eventually become one of the ancestors whom they venerate. Imagine your descendants thinking, “She is the one who broke the cycle, the one who rose above her pain and disadvantage to give all of us a better life.” To me, that’s a beautiful thought, one that should make you stand up a little straighter and hold your head a little higher and try a little harder.

A: Okay, final question. Some people may feel like ancestor worship is all well and good in small doses, but that ultimately it is too inward-looking, that, for example, it may inflame national divides if taken too seriously. They might also argue that we are now facing a number of species-wide problems that can only be solved if we unite behind truly universal narratives and histories. How would you respond to these criticisms?

Q: I think they are fair and we should in fact be worried about the possibility of the antiquarian slipping into the critical, but at the same time, revering one’s ancestors and reviving past grievances are distinct activities and one doesn’t have to imply the other. I also agree that a new story is needed, something which calls us to recognize our shared humanity and allows for increased coordination around pressing global issues.

At the risk of sounding like the man with the hammer for whom everything is a nail, I would argue that we might again use antiquarianism and ancestor worship practices to begin weaving this new human story. The guiding question here might be something like: what activities, rituals, sacraments, etc. can we institute that will begin to effect this global shift towards sapien consciousness (as we might call it)?

I have one modest proposal in this regard, and we can end on this—let’s rekindle the most ancient of rituals, one that our ancestors have been doing for eons: sitting around a fire at night with our loved ones and telling stories.

This practice is so ingrained in the human psyche that we never truly gave it up and probably couldn’t even if we tried—only now instead of gazing into dancing fires and listening to our elders, we gawk at glowing screens and watch movies. What I’m proposing then is that once a year, once a month, or better yet once a week, we get together with our friends and family (our tribe), and simply tell stories—and not just ghost stories (although we can tell those too) or other fictions, but histories, myths, and scientific stories, any story that illuminates and affirms our common humanity, any story that reminds us of the billions of Homo sapiens who died so that we may live. At first, our stories will be awkward and stilted, but we are natural storytellers and it won’t take long for our narrative faculties to regain their former strength. We will remember how to imagine, how to dream, how to hope. We will remember that what is worth living for, what is worth fighting for, can be found here in our flesh and blood around the flame.

Epilogue

In closing, I thought it might be useful if I provided an example of my own personal ancestor worship which illuminates some of the themes discussed above. In particular, I want to share two documents from my family’s history that have a special significance to me. The first:

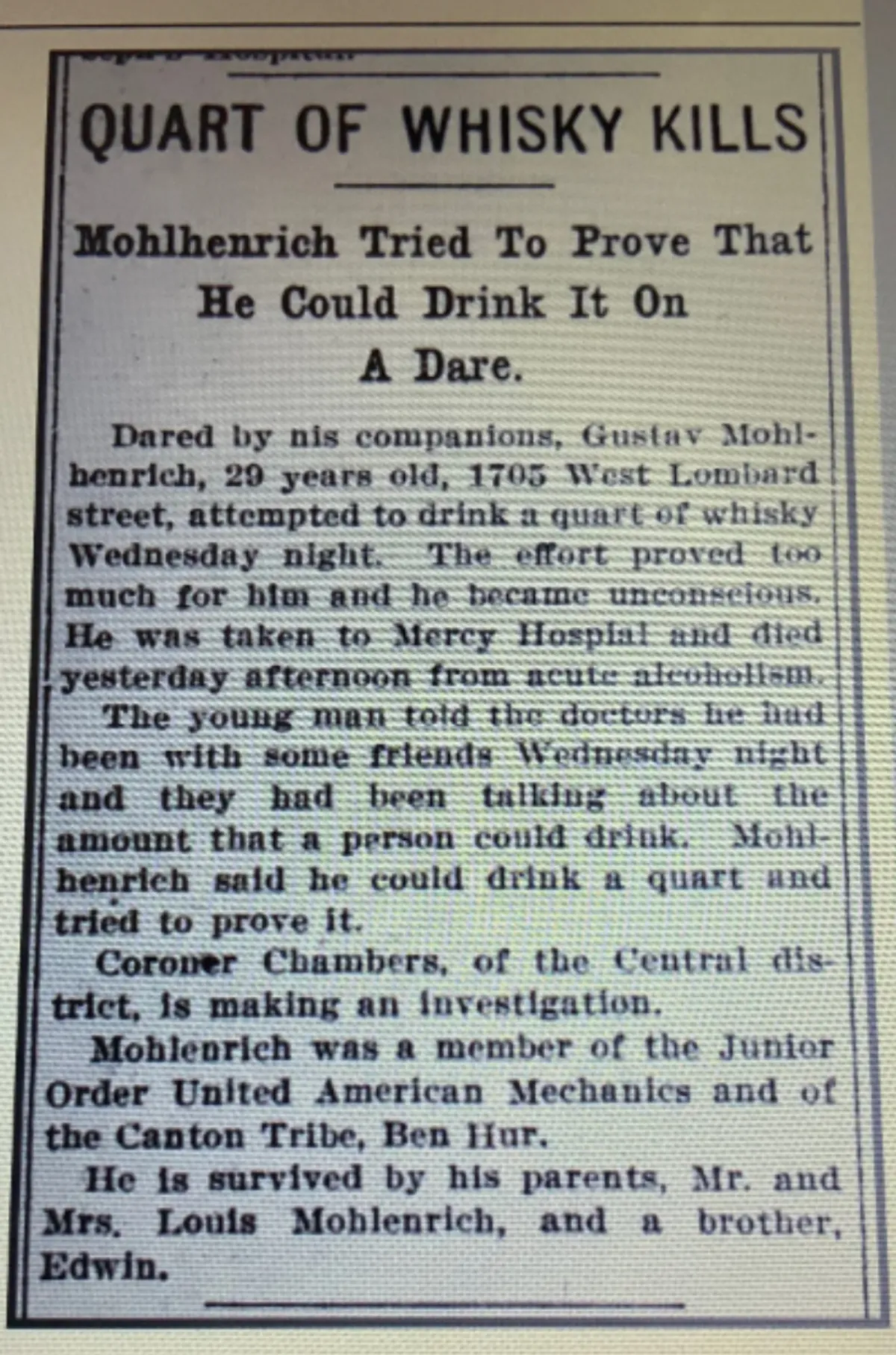

We aren’t 100% sure about who Gustav was and what year he died, but it was likely around 1910 and he was some kind of relative of my great-grandfather. There are a few reasons why I treasure this document. For one, no disrespect to the big homie Gustav, but the tragedy has faded and we can admit that it’s more than a little funny. Say what you want about his intelligence and judgment, but the man had fortitude and competitive spirit. I know Valhalla is typically reserved for those who die in battle, but I’d like to think they made an exception for ol’ Gustav. The news story also makes me laugh because they botch the spelling of the surname, using Mohlhenrich and Mohlenrich in different instances, which I can relate to because people have been forgetting that pesky second “h” my entire life.

But on a more serious note, Gustav’s story is important to me because alcoholism still runs in my family. I am filled with immense gratitude and pride when I think about how my dad and some of his siblings overcame a generational disease in order to provide a better life for my cousins and I.

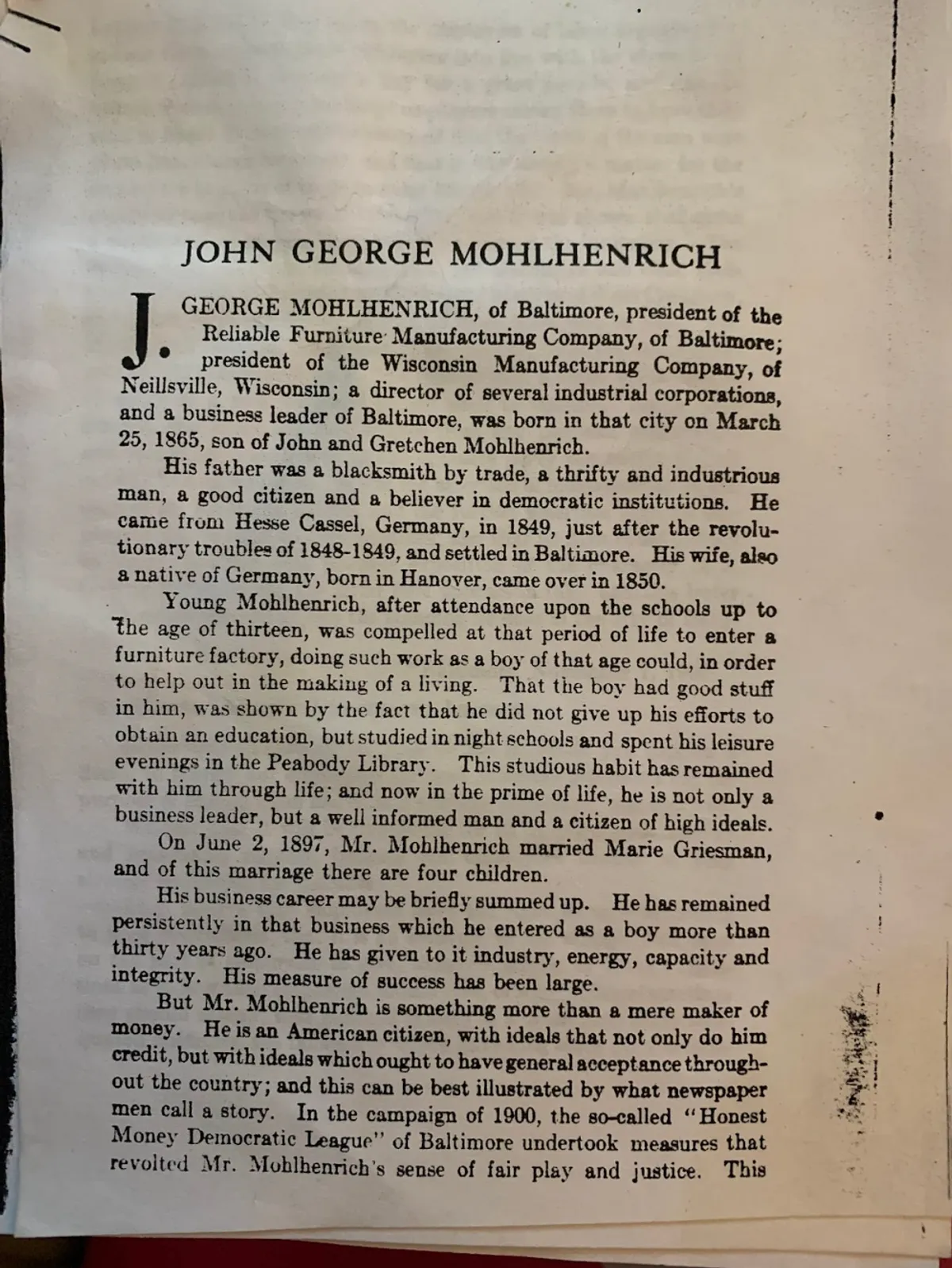

The second document is a short biography written about my great-great-grandfather, son of the first Mohlhenrich to come over from Germany.

Unfortunately the Reliable Furniture Manufacturing Company closed down during the Great Depression and I am not in fact the scion of a furniture dynasty, but given that I have spent my life as a scientist, teacher, and writer, I do like to think that some of John George's studiousness did get passed down to myself, through both genes and an unbroken chain of Mohlhenrich children learning the habit from their parents. John George’s story also serves as a valuable reminder of how good I had it as a kid (I was complaining about school and playing countless hours of video games when I was 13 while JG was working in a furniture factory and spending his evenings in the library by choice) and as a source of inspiration for when I’m feeling unmotivated by whatever piece-of-cake work I have to do (like finishing this essay)—I just imagine John George looking down on me from a heavenly firmament with a stern face, shaking his head in disapproval at my laziness.

It's also hard not to feel a measure of pride and patriotic sentiment when thinking about how this first-generation German immigrant came to be such an exemplar of American ideals and a pillar of his community. The story about the “Honest Money Democratic League” (which doesn’t sound shady at all), including a letter written by JG that is just dripping with delicious sarcasm, is shared in text below:

“…This League brought to bear upon the employers of labor arguments to induce them to force their employees into line with the views of the League. Finally, they set a day for a great parade, and circular letters were sent out to the large employers asking them to have their men in line. It was calmly assumed that the views of the men were of no importance whatever, and that it was simply & matter for the employers to instruct them to enter the parade. Mr. Mohlhenrich's company received the usual invitation, and it was shown that quite a number of employers had promptly accepted the invitation. The cotton duck trust, the tobacco trust, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the South Baltimore Car Works, the Maryland Steel Company, and other large employers, agreed to have their men in line. Mr. Mohlhenrich received under the date of October 31, 1900, the usual letter sent to the other employers. He replied with a letter which was as effective as a two thousand pound shell in warfare (emphasis mine). As he says himself, the letter was not written from any partisan standpoint, and would have been sent to the opposite party committee if their actions had called for it. It was the assertion of independence on the part of an American citizen, and the further assertion that his employees had a right to their opinions, and that no man could dictate to them. As the best possible exposition of the character of J. George Mohlhenrich, the letter here appears in full: and this letter. will explain why he enjoys the standing he does in the city of Baltimore:

Baltimore, November 1, 1900.

THE HONEST MONEY DEMOCRATIC LEAGUE:

Gentlemen: Yours of the 31st ultimo in which you express a desire to borrow our employees for next Saturday afternoon for the purpose of having them march in a political procession, was received. We fear that it will be impossible for us to grant your modest and reasonable request, because our employees believe in very strange doctrines; for instance: They believe that employees have the right to vote according to their convictions; that it is an evidence of exceedingly bad taste on the part of employers to give, unasked, advice or make suggestions as to how their employees should vote, or what political meetings they should attend; that political bribery is a crime; and other antiquated doctrines, the fallacies of which have long since been demonstrated by so eminent an authority on modern political ethics as Mr. C—.

If, therefore, we were to ask our employees to march in the procession, they would perhaps have the effrontery to ask under what colors they are expected to march, as though it should make any difference to them whether they march under the colors of one party or the other.

And after that question was answered, some of them might even venture to tell us such irrelevant stories as: “The Hebrew manufacturer who ordered his Gentile employees to march to his synagogue on a certain day to be circumcised,” and “the Catholic manufacturer who 'requested' his Protestant employees to march in body to his church, and sprinkle themselves with holy water,” and after they have told us these stories they would leave us to guess at their application.

If you find on Saturday that you are still short of men, we would suggest that you send someone to Marsh Market Space, which is not far from this factory, and there you will find some gentlemen who are not so oversensitive as our men. They will march in a procession without asking any impertinent questions about the colors and they may even go a step further, and vote for any candidate which the Honest League may designate, if by so doing they could make an honest dollar.

Respectfully yours,

THE RELIABLE FURNITURE Mfg. Co.

J. George Mohlhenrich,

President.

Footnotes

[1] The wider context of the Jacques Barzun quote:

“All that is meant by Decadence is “falling off.” It implies in those who live in such a time no loss of energy or talent or moral sense. On the contrary, it is a very active time, full of deep concerns, but peculiarly restless, for it sees no clear lines of advance. The forms of art as of life seem exhausted; the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully. Repetition and frustration are the intolerable result. Boredom and fatigue are great historical forces.

It will be asked, how does the historian know when Decadence sets in? By the open confessions of malaise. When people accept futility and the absurd as normal, the culture is decadent. The term is not a slur; it is a technical label.”

[2] Continuing this theme later on, Nietzsche writes:

“Modern man suffers from a weakened personality. Just as the Roman in the time of the Caesars became un-Roman with regard to the area of the earth standing at his disposal, as he lost himself among the foreigners streaming in and degenerated with the cosmopolitan carnival of gods, customs, and arts, so matters must go with the modern person who continually allows his historical artists to prepare the celebration of a world market fair. He has become a spectator, enjoying and wandering around, converted into a condition in which even great wars and huge revolutions are hardly able to change anything momentarily. The war has not yet ended, and already it is transformed on printed paper a hundred thousand times over; soon it will be promoted as the newest stimulant for the palate of those greedy for history. It appears almost impossible that a strong and full tone will be produced by the most powerful plucking of the strings.”

Hard to believe he was writing in 1874 and not in 2002 with reference to the War in Ukraine and our current technological milieu.

[3] Nietzsche: “Antiquarian history knows only how to preserve life, not how to generate it. Therefore, it always undervalues what is coming into being, because it has no instinctive feel for it, as, for example, monumental history has. Thus, antiquarian history hinders the powerful willing of new things; it cripples the active man, who always, as an active person, will and must set aside reverence to some extent.”

[4] Gurwinder calls it “Intellectual Obesity”:

“Just as gorging on junk food bloats your body, so gorging on junk info bloats your mind, filling it with a cacophony of half-remembered gibberish that sidetracks your attention and confuses your senses. Unable to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant, you become concerned by trivialities and outraged by fiction. These concerns and outrages push you to consume even more, and all the time that you're consuming, you're prevented from doing anything else: learning, focusing, even thinking. The result is that your stream of consciousness becomes clogged and constipated; you develop atherosclerosis of the mind.

We now live in a state of constant distraction caused by an addiction to useless information, and this distraction is so overpowering it even distracts us from the fact we're being distracted. You'll probably read this article, briefly consider the damage junk info has done to you, and then return to aimlessly scrolling Twitter”

[5] How do we make things cool again? What comes after postmodernism? One answer: a turn towards Metamodernism–the balancing of ironic detachment with sincere engagement. Here is David Foster Wallace from his 2006 essay “E unibus pluram: television and U.S. fiction”:

“The next real literary “rebels” in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Dead on the page. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that'll be the point. Maybe that's why they'll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk disapproval. The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. Today's risks are different. The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the “Oh how banal”. To risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of overcredulity. Of softness. Of willingness to be suckered by a world of lurkers and starers who fear gaze and ridicule above imprisonment without law. Who knows.”